A residential neighborhood in North Minneapolis is split in half by six lanes of roaring traffic on highway 55. Our Streets Minneapolis envisions a future for the urban highway that fosters community and puts people first.

Our Streets Minneapolis, located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, is a nonprofit organization that tackles the challenges of commuting in a car-centric city. They work to make changes to legislation that increases the viability of biking, walking and public transportation in the city.

Long has America loved its cars. From cross-country road trips to late-night fast-food visits, they provide people with the independence to go where they want, when they want.

But what of those that cannot afford their own cars? What of those that do not want to own cars that contribute to the climate crisis?

The United States’s car-centric infrastructure sets a precedent of high economic and environmental costs for transportation. The agency to travel even within compact urban areas is monopolized by cars.

Because of car-centrism, more affordable and environmentally friendly alternatives to driving such as riding the bus and biking, do not fit the transportation needs of commuters.

Our Streets Minneapolis runs a campaign for the removal of highways called Streets for People.

Streets for People focuses on universal design which empowers local communities that will be affected most by the change, says Carly Ellefson, the Communications Manager for Our Streets Minneapolis.

Urban areas have been responsible for about 80 percent of total vehicle CO2 emissions growth in the United States since 1980, according to Climate Central.

Olson Memorial Highway is an urban highway that runs through North Minneapolis and has divided the community since its construction began in 1939. The highway has created a hazardous environment for residents through dangerous crossings and poor air quality, says Ellefson.

Highways create extreme heat and poor air quality, says Ellefson. The risk of developing respiratory illness such as asthma from toxins associated with traffic is 3.4 times higher in areas less than a mile from a highway, according to ABC News.

Our Streets Minneapolis brings attention to the health, safety, and environmental struggles caused by Olson Memorial Highway through their Bring Back 6th campaign.

“Part of it is doing extensive storytelling in public history about what was destroyed so that people really understand the cost of their commute,” says Ellefson.

The Bring Back 6th campaign aims to reduce each side of the highway down from three lanes of traffic to one and add designated, 24/7 bus lanes. The campaign envisions wider sidewalks, an off-street bike lane and a decreased speed limit of 25 miles per hour.

These changes would increase safety for residents by reimagining the road to be people-centric. Less lanes of traffic and a lower speed limit also decreases the amount of dangerous toxins from highway traffic.

Commuting by bicycle is made more accessible by off-street bike paths that increase road safety for bikers, and designated bus lanes increase the reliability of public transportation as a primary mode of transportation.

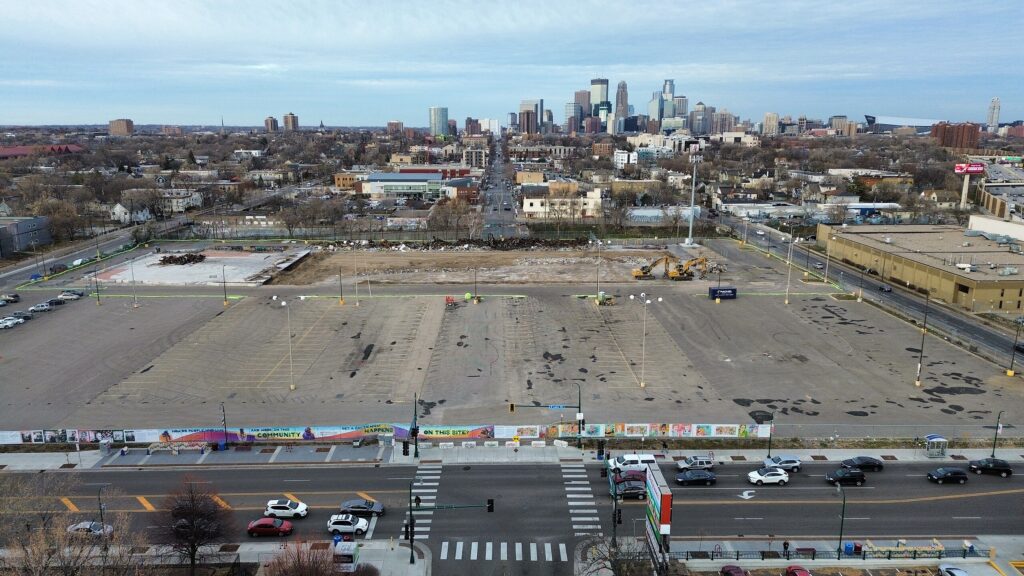

Another area of interest for Our Streets Minneapolis is the K-mart on Lake Street and Nicollet Avenue in Minneapolis.

What was once a high traffic area became nearly car free thanks to the construction of the K-mart in 1977 which interrupted the flow of Nicollet Avenue, according to Star Tribune. The urban planning was criticized by Minneapolis residents at the time.

The blockage of Nicollet Avenue created a perfect low traffic area in the south part of Nicollet, says Ellefson. The area is now referred to as Eat Street and provides a popular city space for people to commute on foot.

“Basically, it was like a happy accident of not creating a high traffic area,” says Ellefson. “An urban planning blunder turned into a good thing.”

The city bought out the store’s lease for $9.1 million in 2020 and has released potential plans for redesigning the street. Three designs would return Nicollet Avenue to a car-centric street while one design envisions the street as car-free.

Our Streets Minneapolis promotes a car-free vision, saying that if cars are permitted to cut through the K-mart site, it will increase safety risks on Nicollet Avenue and ruin the character of the vibrant business district.

“A big part of our streets for people is getting people involved in the street design process,” says Ellefson.

The organization’s car free vision for Nicollet Avenue champions greener transportation including a transit bus lane and connections to the current bikeway, says Ellefson.

These initiatives from Our Streets Minneapolis provide insight into city planning that puts people at the center of eco-friendly practices. Decreasing health and safety risks caused by car-centrism is at the forefront of their vision for Minneapolis.

More highways and traffic lanes are not the answer to improved transportation. As much as Americans have become used to their cars, Our Streets Minneapolis calls for a change in the precedent.

By removing highways and modifying streets to restrict the access of cars, Minneapolis could set an example for large urban areas by encouraging the use of public transit and biking to give people the agency to commute in greener ways.