One concept which confounds many people in discussions around climate change and global warming, is that a rise of 1.5°C could be significant. I’ve never known a single day in my life where there’s not been greater variation than that, let alone then talking about seasonal variations in temperatures. So it’s no wonder that an average increase of a paltry 1.5°C leading to disaster is a difficult concept to come to grips with.

The global average temperature has been recorded since the mid to late 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution was really kicking off. But temperature measurement was happening for centuries before this in various parts of the world. Measurements were originally taken from land and ship instruments, but now includes ocean buoys and satellites too. Scientists use 4 major datasets to study global temperatures:

* The UK Met Office Hadley Centre and the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit jointly produce HadCRUT4;

* the GISTEMP series comes via the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Sciences (GISS);

* the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) creates the MLOST record; and finally

* the Japan Meteorological Agency ( JMA).

For a great explanation of the complex process of aggregating this data into global trends, head here.

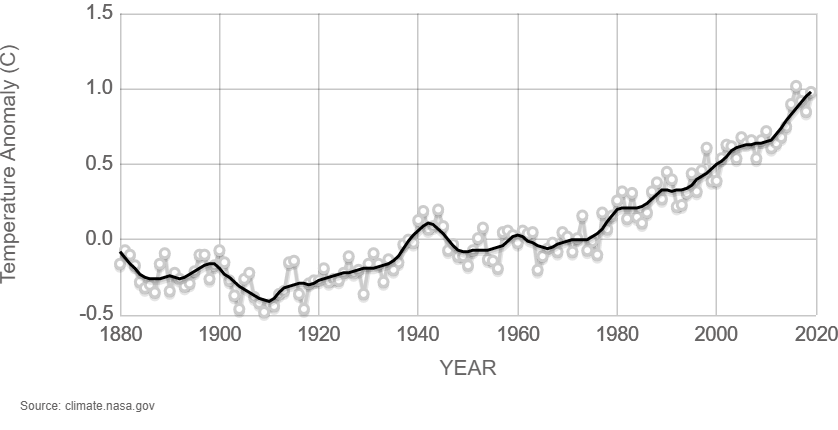

So back to this oddly worrisome 1.5°C rise. It has been confirmed by the very trustworthy sources above, that over the last 140 years we’ve seen an average global temperature rise of 1°C. But two thirds of that warming has occurred since 1975. This might go part way to explaining why some of the Baby Boomer generation don’t think we’ve seen a great deal of temperature (or climate) change – were they able to compare to 20 years prior to 1975, there might be a more stark, less subtle difference to now. But in those 20 years, most were teens, so noticing temperature trends was pretty unlikely.

Numbers don’t lie: we’ve seen the 20 warmest years on record since 1981, and the warmest 5 years were 2014-2018.

With the current increase of 1°C we’ve seen huge changes in our environment: more frequent and more droughts, floods and extreme weather events like bushfires and hurricanes; upper level ocean temperature rising; sea level rise and biodiversity loss. We’re experiencing reduced ability for agricultural success and we already have climate refugees. We have seen changes in the patterns of migratory fish, which in turn reduces the numbers of the bird life and other ocean creatures who feed on them. We’re noticing increases in pests, like mosquitos, ticks and bark beetles, bringing disease or destruction of forests.

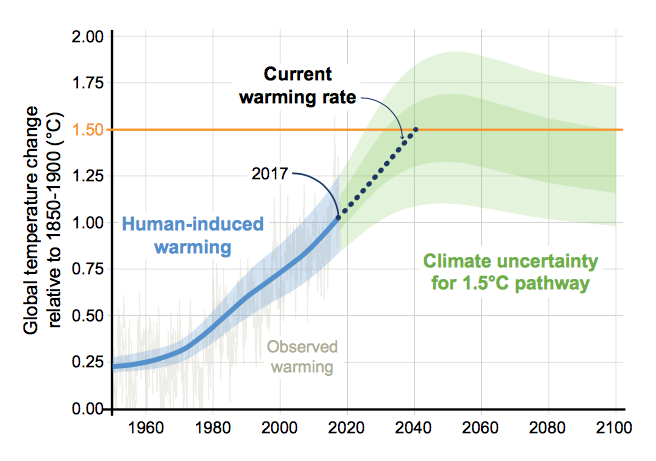

Based then on these already widespread and dangerous effects, it’s clear we need to stave off further rise as much as we can. But unfortunately the horse has bolted on stopping that altogether. Even should we completely cease anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions right now, today, the path for temperature rise has been set: we would be likely to still hit the 1.5°C of warming over the next century. That’s because of the GHGs which are already in the atmosphere, and depending on which one, the impact from it will be seen for decades or tens of decades.

So, at the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in December 2015, which took place in Paris, 195 nations agreed upon the Paris Agreement. The crux of this was “holding the increase in global average temperature to well below 2°C … and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” However it had already been documented by the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) in 2010 (the Cancun Agreement, which came from COP16) that although current limitation was set to 2°C, there should be awareness that strengthening the limitation of warming to 1.5° may be necessary. And indeed, after a 2 year review from 2013 to 2015, that recommendation was made. If no further increases to anthropogenic GHGs were made, our current trajectory sees us hit 1.5°C of warming by about 2040. If we are to prevent an overshoot of this, we need to have reduced our GHGs by 45% of 2010 levels by 2030, and be actually net zero GHGs by 2050.

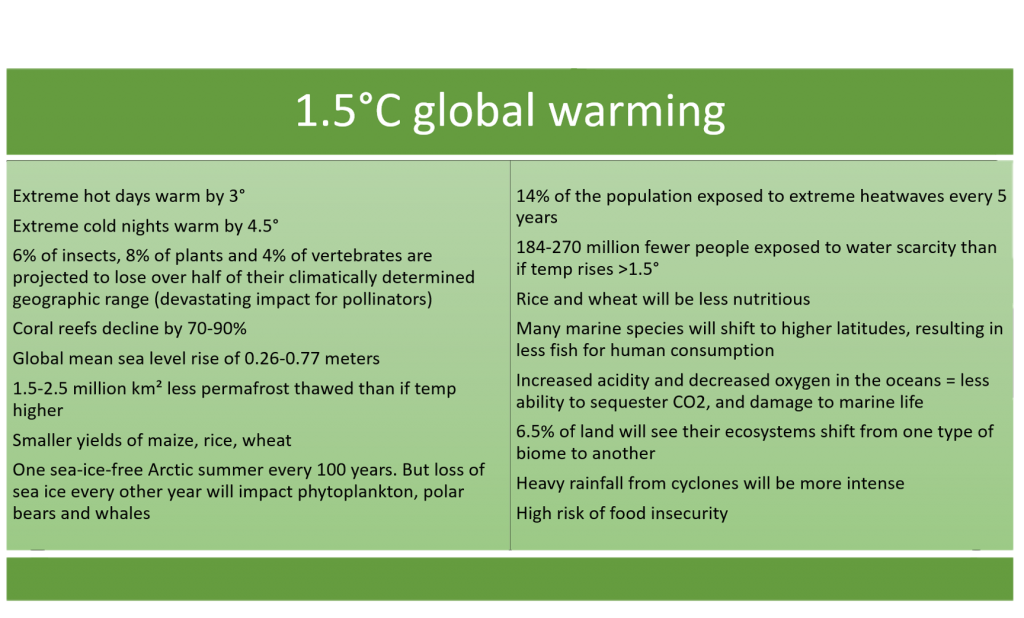

What can we expect then, from a further 1.5°C average global temperature rise? Nothing good. The UNFCCC requested that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on what global warming at 1.5°C and beyond would look like. See the table for a pretty confronting picture. This has all been summarised from the aforementioned IPCC Report, but is not an exhaustive list of global warming impacts.

There are 3 important things which must be remembered to understand the importance of 1.5°C temperature rise:

1. This is the global average, across the whole surface of all the land and sea. To actually achieve the global average to rise 1.5°C, we need to see an immense rise in heat. Very many places will experience local temperatures much much higher than 1.5°C above average – dangerously hot – and in some places this has already happened.

2. There is a very fine balance required for all things on Earth to be successful or thrive. That includes temperature. The human body is a great example of this – with a very small 2°C rise, we become largely incapable of functionality. Sea turtles are another example – if the sand where the mother lays her eggs is 31.1°C, all females are born, but if the sand is 27.8°C and lower, all males will hatch!

3. This reflects a trend. There will be colder days, months, and maybe even a colder year or two…but the trend is unarguably an upward trend.

So with these cold hard facts, we must not be paralysed by fear and anxiety, but spurred on to ensure global leaders take action. Every one of use has power to change our own emissions path and hence make a contribution to the bigger picture. But we also have powers to demand systemic change. Email letters; sign petitions; front up at your local elected official’s office, in a group, with a hand written letter; write to your local manufacturing plants to install renewable energies; protest new coal, oil and gas power; and VOTE.

We have 9 more years to make sure we can flatten another curve. Let’s give it a damn good go!