In 2018, the United States ascended to the title of the world’s primary crude oil producer, surpassing long-time competitors Russia and Saudi Arabia. While hailed as a significant milestone in pursuit of U.S. global supremacy, this feat is accompanied by a series of pressing environmental concerns.

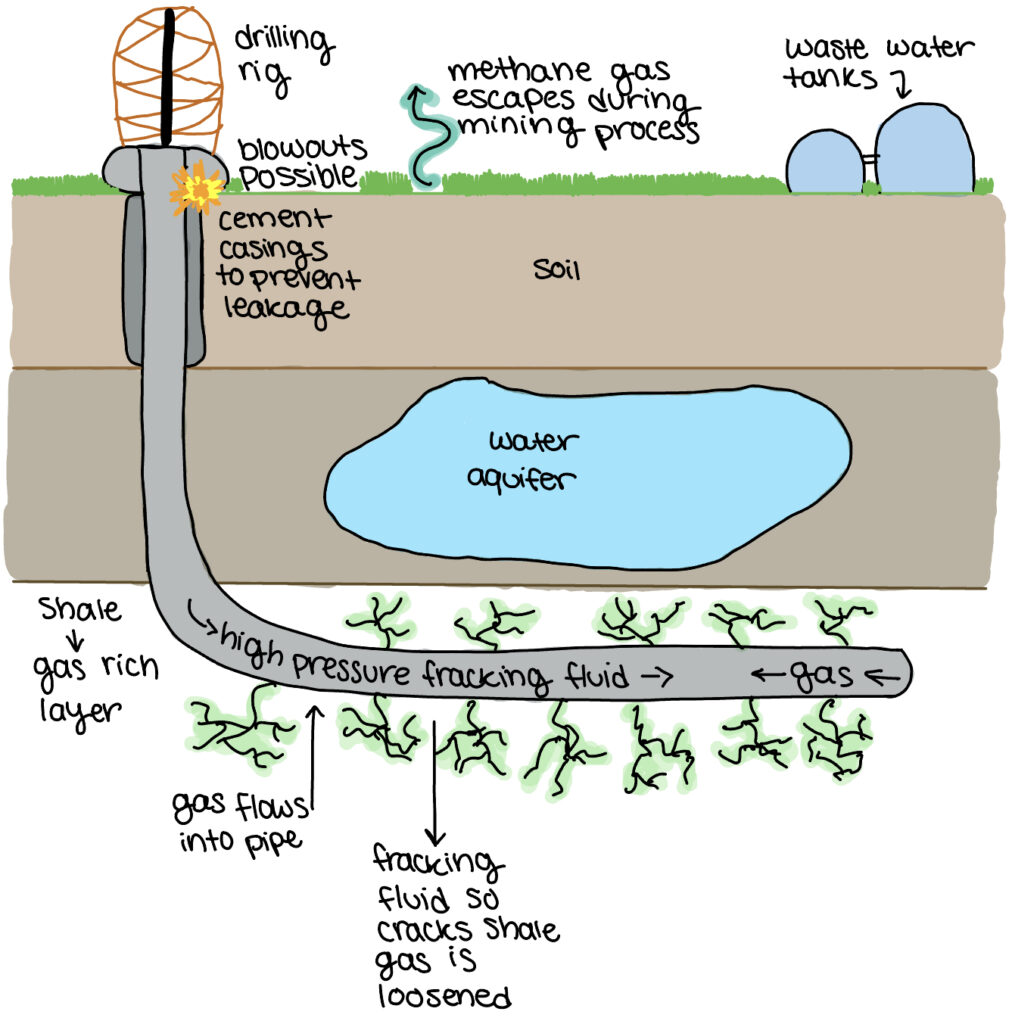

Hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking, is a method used to extract oil and natural gas from Earth’s depths. It involves injecting a high-pressure mixture of sand, water, and varying chemicals into the ground to fracture rocks, allowing resources trapped within them to float to the surface.

Fracking has completely transformed the global energy landscape, as it unlocks vast reserves of natural gas and oil previously assumed unreachable and inaccessible. Despite its innovation, this extracting technique has been fraught with ongoing human safety concerns, environmental controversies, and political debates.

The History

The idea of fracking, originally known as “shooting the well,” traces its origins back to the early 1860s. Development of the earliest forms of fracking are credited to U.S. Civil War veteran Colonel Edward Roberts, who was observed the impact of artillery on narrow, water-filled channels during the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Years later, Roberts translated his discovery into the development of an “exploding torpedo,” which was 15 to 20 pounds of gun powder packed into an iron cylinder, designed to be lowered into oil wells and detonated, effectively shattering surrounding rock formations, according to the National Resources Defense Council.

Robert’s invention was a continuing success and served as a revolutionary turning point in the nation’s oil industry. Roberts and his brother eventually established “the Roberts Petroleum Company” in 1866 after being granted sole rights to use their torpedoes from the U.S. Supreme Court, as per the Philadelphia Area Archives.

In present day, Roberts is recognized as a visionary who laid the foundation for the evolution of fracking. Though it is George P. Mitchell, an esteemed American businessman and real estate developer, that is currently known as “The Father of Fracking.”

In 1991, Mitchell revolutionized the movement by introducing a combination of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques. These techniques would eventually make him a billionaire.

Mitchell’s company, “Mitchell Energy & Development Corp.,” alongside their unconventional drilling techniques, developed economically feasible production of natural gas from the Barnett Shale in the 1990, as per the International Association for Energy Economics.

The Barnett Shale, according to the Railroad Commission of Texas, is a geological formation covering 5,000 square miles of Texas. Considered one of the largest natural gas fields in the country, the area has been extensively developed for natural gas extraction through fracking.

Mitchell’s work in the oil and gas industry successfully orchestrated a transformative resurgence of the fracking process, fundamentally altering the landscaped of energy production into the 21st century.

The Process

Fractures in rock formations that stimulate the flow of natural gas or oil are induced through injecting substantial volumes of fluids under high pressure down a wellbore and into the intended rock formation, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This process of fracturing sufficiently disrupts rock formations to enable the extraction of oil and gas.

The fluid used is fracturing is a sophisticated blend, primarily consisting of water and a proppant, which is a granular substance consisting of uniformly sized particles – usually sand. These particles are used to prop open the fractures created in the rock, and since they are uniform, they allow oil and gas to flow in between their spaces and into collection wells.

According to the American Geosciences Institute, the sand, often referred to as “frac sand” is mainly mined in the Great Lakes Region of the United States, consisting of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois.

In Southeast Minnesota’s Winona County, a committed group of community members created the “Land Stewardship Project,” with one of their goals being to prohibit frac sand mining within the reason.

“In order to do fracking, you have to have a particular kind of sand, and Southeast Minnesota and Southwest Wisconsin are one of the few areas in the world who have that sort of sand,” said Brian DeVore, the project’s managing editor and media coordinator.

According to DeVore, fracking enterprises would travel to these regions, extracting the upper layers of hills and other sandstone deposits to procure sand and send it to major fracking sites, such as those in Texas and North Dakota.

Devore described the practice as “a real unproven way of mining,” and said that he has not seen anything like it in Minnesota.

In a comprehensive Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) compiled and signed by 100 members of the project, citizens articulated their apprehensions regarding the ramifications of frac sand mining on local air and water quality, land destruction, transportation conditions, economics factors and overall community well-being.

“As has been well documented, air and water have been polluted, farmland and landscapes destroyed, the integrity of public officials and public processes severely undermined, local economies threatened, and quality of life diminished, all for the benefit of corporate oil and gas interests,” the group wrote.

DeVore said that after a year-and-a-half long battle, the group was able to get frac sand mining completely banned in Winona County in 2016 after majority of the Winona County Board of Commissioners voted in their favor. It was the first county in Minnesota to take such a position.

Following the ban, a four-year battle ensued between the Winona County Board and Minnesota Sands, the primary sand mining business involved in the issue.

According to Minnesota State Legislature, the Minnesota Supreme Court voted to uphold Winona County’s ban on frac sand mining on March 11, 2020. The Court concluded that the ban did not infringe on the rights of Minnesota Sands.

In 2021, Minnesota Sands attempted to carry their case against Winona County to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the Court declined to take the case.

Alongside the frac sand, fracking fluid contains several chemicals. According to the Department of Mines and Petroleum, the chemicals are added “to improve the transportation of sand, prevent growth of bacteria, reduce mineral or chemical blockages and to avoid well corrosion.”

After a rock formation is fracked, the fractures created in the rock allow oil or natural gas to flow freely toward the wellbore. These resources are then extracted to the surface for processing. The wells often produce oil or natural gas long after the rock formation is fracked, but rates of production typically decline as reservoir pressure decreases over time.

Public concerns surrounding health, water safety, and other factors have prompted scrutiny of the fracking process and its post-operation effects.

The Controversy

As the global demand for energy continues to rise, fracking has proved to have several economic benefits and has played a significant role in the U.S. quest for energy independence. However, the practice has sparked multifaceted debate over its post-operation effects.

The rise of concerns regarding induced earthquakes, air pollution and water pollution highlights potential risks to human health stemming from fracking practices. Along with this, communities and environmental groups have grappled with the impacts on wildlife and ecosystems.

Though earthquakes are not directly caused by the process of fracking itself, the disposal of waste fluids after the fact has caused an increase in earthquakes in the central U.S., according to the United States Geological Survey.

These fluids, byproducts of the oil production, are often left in wastewater disposal wells. These wells are used to dispose of both produced waters, which are waters extracted alongside the oil and gas, and flowback waters, which are waters that immediately return to the surface after the fracking process, as per the American Geosciences Institute.

These wells, according to the United States Geological Survey, “typically operate for longer durations and inject much more fluid than is injected during the hydraulic fracking process, making them more likely to induce earthquakes.”

Marc McCord, director of FracDallas, said that once water is used in the fracking process, it can’t be reused. It becomes permanently polluted. Fracking companies will inject it back into the ground using deep injection wells, which contributes to earthquakes.

McCord uses Oklahoma as an example, noting that for a period of three to four years, Oklahoma experienced a notable increase in earthquakes due to wastewater from fracking sites in Texas. As the time, Oklahoma’s seismic activity passed California’s – a state known for its high levels of seismic activity.

However, earthquakes aren’t McCord’s sole concern. Across various fracking operations and depending on the formation being fracked, they utilize up to 969 different chemicals, although not all deployed in a single well.

“These [chemicals] are toxic, carcinogenic and neurotoxic. They’re not things you want in your drinking water, they’re not things you want in the soil where your food has been raised and you don’t want them in the air you’re breathing,” he said.

McCord highlighted the findings of several studies indicating that people residing near fracking wells may experience a higher incidence of health issues due to air pollution from fracking sites.

More vulnerable populations, such as children and elderly, are more at risk for these health issues because they have fewer defenses against exposure to pollution. Air quality tests at playgrounds near fracked wells in Texas found elevated levels of benzene, a known carcinogen, according to the Frontier Group.

The group outlines various potential health and safety risks of fracking resulting from air pollution, detailing some of them as follows:

• Hazardous air pollutants from equipment, trucks and wastewater

• Airborne silica sand

• Elevated levels of cancer-causing radon

• Exhaust from flaring or venting natural gas

• Diesel soot from trucks and equipment

“It looks like a simple issue on the surface,” McCord said, “but once you get into it, one thing leads to fifteen other things.”

Image credit: Bruce Gordon at EcoFlight ecoflight.org/photos/

John Fleming, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, asserts that the detrimental chemicals deployed in fracking have the capacity to contaminate both our air and water sources. He said that water is harmed in two distinct ways through the fracking process.

Fracking requires a lot of water, so millions of gallons of freshwater are taken just for the process. The water that comes back up – the produced water – is then contaminated with the several chemicals injected into it.

At that point, you can’t put that water to beneficial use anymore, so it’s often re-injected into the ground for storage, he said.

“The second way that you’re threatening water is that during the process of fracking,” Fleming said, “you’re opening up pathways to freshwater resources for these chemicals to flow.”

McCord of FracDallas also raises concerns about water contamination through fracking procedures, pointing out that only about 0.2% of Earth’s water is usable freshwater. He stresses that the rest of the water is excessively salty and briny, rendering it unusable in any financially practical way.

Once water is utilized in well drilling, he explains, it becomes unsuitable for consumption, farming use, bathing, or any other essential purposes requiring clean water.

“At a time when the well population is growing like it is and the water shortages are as great as they are,” McCord said, “the very last thing you need is your drinking water being contaminated.”

“People will fight for oil, but people will kill for water. The water is the issue, above all else,” he said.

Though humans aren’t the only life forms effected by fracking procedures – wildlife are to be considered as well.

While human communities bolster the brunt of the impacts from fracking operations, it’s imperative to recognize that wildlife also face consequences. The extensive disruption to habitats, including destruction and pollution, can profoundly affect several species.

People should raise concerns about wildlife concerning not only fracking, but all oil and gas development. The simplest point, Fleming said, is that land is being disturbed through all of these processes.

“You’re disturbing where wildlife live,” he said, “and you’re dealing with other aspects like air quality harms and water quality harms, of course animals can be affected by those as well. It’s important to keep animal and human harms in perspective when talking about oil and gas development in general.”

Considerations

The journey of fracking, encompassing its process, evolution, and debates, reflects a nuanced, complex story. Though it emerged originally as a groundbreaking oil and natural gas extraction technique, discussions concerning environmental implications and public health issues have plagued its glory.

While proponents praise fracking’s economic benefits, innovative technology and contributions to oil security and independency, opponents raise several concerns highlighting environmental impacts, risks to human health and impacts on wildlife systems.

“Fracking means we’re continuing to prolong our reliance on fossil fuels,” Fleming said, “and fossil fuels are contributing to climate change, which is affecting humans and wildlife.”

With thanks to these interviewees: Brian DeVore, Land Stewardship Project; Marc McCord, FracDallas; John Fleming, Center for Biological Diversity.