There can be no question that the human population are hesitant, to say the least, about dramatically changing our ways to consume less power. So it is with increasing fervor that we are looking for ways to produce energy, in pretty similar quantities to what we’re used to, with methods less reliant on fossil fuels and therefore with less emissions of greenhouse gases. And we are #blessed to live on a planet which provides a veritable smorgasbord of natural resources with which to produce said energy: wind, water (through waves or flow), the sun and the Earth’s crust. But one of the most common arguments against any of these methods is the land required. Land is a precious commodity itself! So when we talk about building enormous solar farms on masses of uninhabitable desert, seems like a no-brainer, right? Unfortunately, not quite. But please don’t give up reading here, with the thought of “are you kidding me? I just want a solution already!”. This is not a doom & gloom piece.

There has been talk of building aforementioned solar farms on aforementioned deserts for some time. It’s no easy feat. But the energy capacity is alluring, to say the least. Researchers hypothesized in 2018 that if they could use 9 million km2 of the Sahara Desert for wind and solar energy production, it would provide FOUR TIMES the current demand for global energy every year! They found, through some pretty amazing modeling, that if this project happened the rainfall in the area would increase by double, each year. The lead researcher, Dr Li, said that this would result in vegetation increasing by 20%! How does that happen exactly? Solar panels are dark in color, meaning they have a low albedo (reflecting little radiative energy from the sun back into space), compared with the high albedo of the desert sand. So the panels lead to increased solar energy being absorbed and then extra heat being emitted. This raises the ground temperature causing an increase in the Sahara heat low pressure system, leading to warm air rising, where it then cools off and moisture condenses, making more rainfall.

If the size of the solar farm reaches 20% of the size of the Sahara, all of that extra vegetation triggers a feedback loop. Heat being emitted from the panels causes more precipitation and vegetation growth. This increase in plants leads to an increase in water evaporation, and subsequent increase in rain and yet more plants grow. So it seems like the desert could not only provide power to the Earth’s human, but feed them too?! Not seeing a downside yet? Well this is a prime example of the small size of this blue planet and the interconnectedness of everything on her.

A study published earlier this year found that this new climate created by the solar panels was not limited by geography. That is, these changes—yes, climate changes—would in fact impact the whole globe. Using an advanced Earth system model (ESM: coupled atmosphere, ocean, sea‐ice, terrestrial ecosystem), the researchers found that these effects include global temperature rise, especially over the Arctic, the redistribution of precipitation, which would lead to droughts and forest degradation in the Amazon, northward expansion of deciduous forests in the Northern Hemisphere, weakened El-Niño-Southern Oscillation and Atlantic Niño variability, and enhanced tropical cyclones. The prediction is reminiscent of the global climate around ~6,000 years ago, when the Sahara was greener and wetter.

The researchers admit that there are even other elements of the greener Sahara which they did not model for, like the reduction of dust being blown from the Sahara to places like the Amazon (this dirt carries essential nutrients, but would lessen if not stop altogether in the land was covered in vegetation). On the face of it, a greener, wetter Sahara Desert, with a solar farm capable of powering the Earth’s people sounds good…but a little too good to be true.

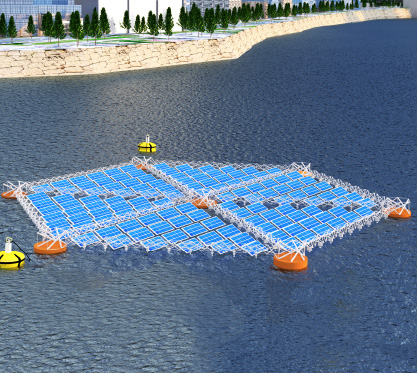

So what next, then? Well one possible answer is locating the solar panels elsewhere. As we know, land is precious, and we can’t take land from human communities. But the ocean is even more vast than the land on Earth. A few years ago, a Chinese company switched on the world’s first floating solar farm. The Sungrow solar farm was placed atop a manmade lake which covers a disused coal mine site, and can power 15,000 homes. Building solar arrays on water helps to solve the heating problem mentioned above, and the internal heating of the cells themselves. It also provides a location which has very little impact on the natural world. But there’s even more available area of water in the ocean, and Dutch and Indian companies are on it! The North Sea is home to the Dutch ‘Zon-op-Zee (Solar-at-Sea)’ and they claim that using only 5% of the North Sea for offshore solar will provide more than 50% of the Netherland’s total energy demands. They also plan to use 5% of the North Sea which is amongst that being used for, or planned to be home to, wind farms. The sun-wind combo is said to have much higher yield of energy that using one alone. They’ve found that floating the solar panels between wind turbines they generate 5 times more energy. Utilizing the same sea-space for the solar and wind farms also means infrastructure to transport the energy is easier and cheaper to install, and maintaining the systems is easier.

India’s project is called ‘Dweep‘, based on the ancient Sanskrit word for ‘island’. That’s relevant because they are developing whole eco-friendly islands of a skeletal like structure allowing for ‘tensegrity’, that is, to be able to flex and move with the ocean. It’s apparently similar to the flexibility our body gets thanks to bones and tendons. These Dweeps can then be used for a myriad of things, like housing an offshore desalination plant, or indeed an offshore solar energy plant. They have already tested a prototype, with promising results, so they’re ready to scale.

As with anything related to abating climate change, divorcing ourselves from fossil fuels and transitioning to a more sustainable future – it’s not straight forward. If it were, I have to assume it would’ve been done long ago! So all we can do is continue to research and try to understand the fine balance and complexity of this planet, to work with it, not against it. And on an individual level, every day we try to do one thing better, with a more learned and sustainable hat on, than yesterday. I urge you to take a step outside, look up, and take in the beauty around you – if you’re in the depths of a city it might not be obvious right away, but I promise there’s beauty in nature close by!