Cities are known as ‘concrete jungles’, with their ever increasing numbers of high rise buildings, mazes of streets and sidewalks, and the rapid decrease in any greenery at all. We accepted that to live in a city meant getting used to a bland palette of grays and blacks, punctuated occasionally with the shine of steel or glass–if sunlight was given a way in. Thankfully, this is changing. Cities are working to shed the concrete jungle label, and find a new greener identity.

It’s not an easy path to take but it’s incredibly worth doing. And of course, as towns grow to become cities with humans tending towards an urban habitat, it’s an important consideration in town planning. Importantly, the benefits are not just environmental, with those people living in a nu vogue city get improved health and well being. It’s been reported on time and again, especially since the start of the pandemic, that having access to greenery and open spaces has a hugely positive impact on one’s mental health. There’s an ever growing library of concrete evidence that living amongst nature, or with rapid access to it, decreases depression and anxiety, reduces feelings of stress and anger, decreases ADHD symptoms, improves sleep, enables better concentration and problem solving abilities, increases the feelings of satisfaction and happiness, and promotes better social interactions.

There’s also robust evidence that your physical health gets a nice boost. Better outcomes for patients with diabetes, improved pain control, better healing, improved immune function, reduced obesity, lower blood pressure, and improved overall general health. Doctors in the Shetland islands of the UK have been prescribing nature to help treat a myriad of physical and mental health conditions since 2018, and now Belgium is jumping on board. In 2019 there were 27 nature based health interventions identified in use across several countries, all with the aim to increase exposure to nature and thus improve health outcomes. Most people know that there’s good reasons to take a walk in the park or do some gardening, but many times the excuse of being too busy is blurted out. However when you have a Doctor’s prescription for the walk or tending to a pollinator friendly garden, you’re much more likely to find the time.

The increase in biodiversity (or part restoration of it, to be more accurate) is obviously very beneficial for the planet. The Earth has been operating with precise balance for millennia. We owe her nothing less than trying to reinstate this wherever we can. Restoring habitats for fauna, ensuring pollinators are catered for, and allowing native and indigenous plants to flourish are all key steps to building a biodiverse rich environment. Cities which embrace a greener identity also see a decrease in their urban heat island effect, thereby reducing the ambient temperature amidst their street and homes. As global warming intensifies, every degree cooler that a city can maintain is potentially life saving. But there’s yet another upshot: as we continue down the path of climate catastrophe we know that food insecurity is almost a given. Bringing food production into our cities, even on a small community scale, will help prevent the worst of the possible food shortages. Growing local and seasonal also offers great benefit from the food emissions and sequestration standpoint. It’s win-win-win.

So where can we look to find examples of cities reinventing themselves and reinvigorating their populations?

Seattle is making some very successful incremental steps to improve the city’s landscape as well as improving water management. They’ve installed porous pavers or concrete for walking paths, side walks, roads and carparks; built rain gardens to utilize all precipitation for the benefit of plants and carefully selected plants for each location; installed green stormwater infrastructure to improve rain runoff and prevent flooding; installed green roofs for rainwater harvesting and to provide food and carbon sequestration; built sloped naturally draining garden beds; and built swales and dams to control movement of water; and lastly, they provide support to residents who’d like to implement rain gardens or improved water management methods. They’ve approached greening the city through a double lens.

Vienna, Austria, was recently crowned the greenest city in the world. Again! 50% of the city is made up of green areas. But it’s not just the immense presence of green which permits this accolade, but the ease of access to public transport (almost half the population uses an annual public transportation pass), smart water management, use of renewable energy, excellent air quality, walkability, an abundance of farmer’s markets and waste-to-energy plants for electricity and district heating. Not to mention that they have equity top of mind too, with a wonderful model for social housing and healthcare, and they’re addressing the inequitable spread of green spaces. Vienna ticks a plethora of sustainability boxes!

Rotterdam in the Netherlands boasts my 2 favorite green city solutions. the first is Dakpark: a park on top of a shopping center on top of a dyke. It provides everything the community needs. The vast park is 1.2 km (0.75 miles) long and 85 meters (109 yards) wide, making it Europe’s largest rooftop park. It has open spaces for picnics, BBQs, a children’s playground and waterfall to splash around in, landscaped gardens, vegetable gardens, and a Warmth Room for those cold days, which is a walled garden with Mediterranean plants, Oh, and a small flock of sheep. Yes, you read that right: actual sheep. Dakpark is beautiful, functional and a master class in eco-architecture.

The second of Rotterdam’s brilliant green solutions is another rooftop, but very specifically for food production. DakAkker is a 1,000 square meter rooftop farm, with organic fruits and vegetables, edible flowers, worm hotels and several beehives. As if that’s not enough, it employs a SmartRoof which enables rainwater control driven by the weather forecast! Rotterdam has stolen my heart with these amazing innovations!

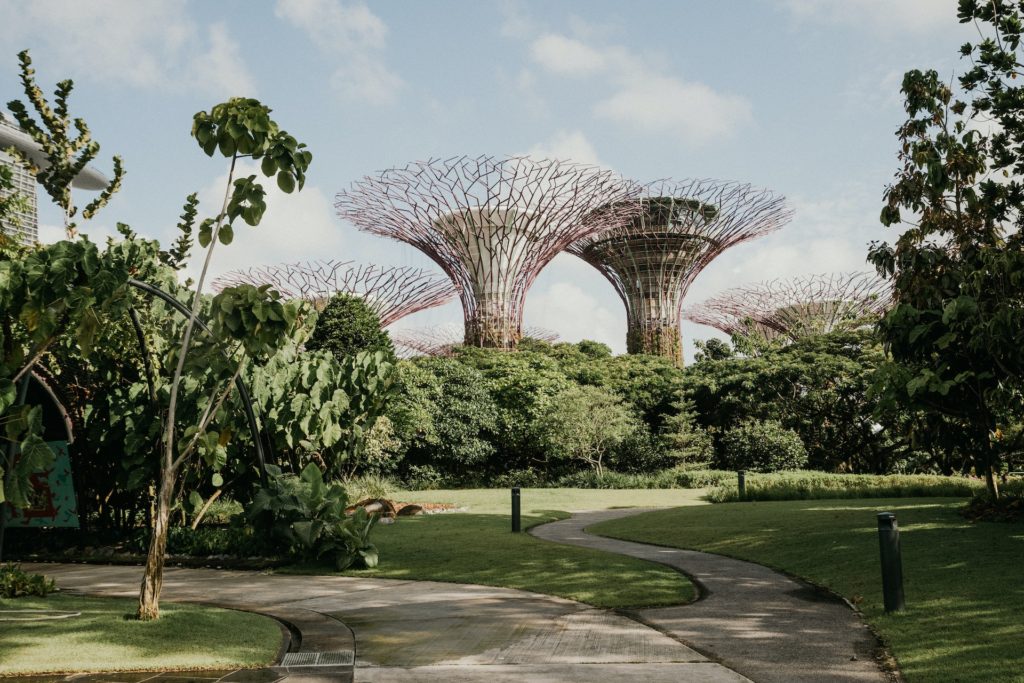

Did you know that Singapore was once home to the most biodiverse mangroves on the planet? In 1953 the Singapore mangrove forests sprawled across an impressive 63.4 square km (24.5 square miles), however by 2018 this area had decreased by a startling 87%, dwindling to only 8.1km2 (3.1mi2). Mangroves are responsible for between 2-4 times the carbon sequestration as tropical forests, so the loss of 87% of this function was frightening. Mangroves also help to reduce erosion from rising sea waters and minimize the damage of floods from typhoons and tidal waves. You can learn more about mangroves and other wetlands here. So to say that the Singapore mangrove forest loss caused great concern in scientific and biological communities around the world is not an overstatement. It therefore came as a great relief when Singapore launched an ambitious reforestation campaign, under the title of a new protected area called the Sungei Buloh Park Network, a 990-acre park in the northern portion of the island. This Network is part of the wider project 1 Million Trees, whereby they’ve signed up to plant 1 million trees in the area over the next 10 years, and want every resident to live within a 10 minute walk of a park. So far, in about 2 years, they’ve planted almost 40% of their target.

For anyone who’s stepped foot in Singapore, this plan and overarching goal is not surprising – for decades Singapore has been an oasis of green. The first tree planting took place in 1963, with the then Prime Minister planting the first tree himself. In 1974 Singapore had 158,000 trees and 40 years later it had 1.4 million! Singapore sits in stark contrast to any other South East Asian country for their meticulous planning and abundance of green. A prominent icon in the skyline is the Pinnacle@Duxton, seven 50-storey apartment complexes which are a public housing project. Each building is joined to the next by a skybridge at the 26th and 50th floors. These bridges are home to gardens, open air gyms, sun lounges, jogging tracks, playgrounds and viewing areas.

There has also been great attention to detail when it comes to water management. If Singapore wasn’t self sufficient for water supply and didn’t clean its once polluted waterways, they would be at risk of water scarcity, relying on neighboring Malaysia for their water. So water reservoirs, parks, sidewalks, rooftops and roads are all used as water catchment: in fact two thirds of Singapore’s surface is for water catchment! The next step in ensuring self sufficiency and sustainability for the country is food. As it stands, much of the lush and beautiful greenery is inedible. So there are plans being implemented to rectify this. An enormous vertical farm, a world first at the time, began commercial operation in 2012 and produces half a ton of fresh vegetables every day. It’s made up of 120 aluminum A-frames each with 38 tiers of food, rotating through the pond it sits in (which catches rainwater and is home to fish) to provide exactly the right amount of water and sun. While many many more of these would be necessary to feed Singapore’s 6 million residents (who live in an area half the size of London!), it’s a wonderful example of what can be done.

Last, but not least, closer to home is the New York City High Line. NYC already has an outsized park with an impressive footprint on Manhattan, but with a burgeoning population increasing human density, there was the need for more green space. The High Line is both a not-for-profit organization and a 1.45 mile long park, repurposing a historic elevated railway line. There are more than 110,000 plants making up the garden, there’s a beautiful walkway and plenty of rest and socializing areas, there’s art and performance, gardening programs and cultural, community engagement. All sitting above the crazy-busy traffic of NYC. This is the smallest project we’ve named, but worth mentioning nonetheless. We start with one small step and build on it.

The increase in greenery in our cities is necessary from several standpoints. Get onto our local municipality to ask for them to do more to improve your air quality, boost biodiversity and increase your quality of life. And do what you can in your own living space, be that window box or backyard. It all helps!