In this race to save the planet from entering climate catastrophe and untold deaths and despair from heat, starvation, and rising seas, many of us are trying to reduce our emissions of heat trapping greenhouse gases (GHGs). This is no easy feat if one wishes to effectively participate in current society, like holding down a paid job or attending school, because current society is built on carbon intensive infrastructure. The fact is, carbon emitting activities make up much of our day.

So then if we (meaning countries and corporations) can’t effectively reduce emissions in the volumes required, what other options are there?

Enter the Carbon Market.

This essentially came to exist on the back of the Kyoto Protocol. Check out our previous piece which explores this and other environmental protection treaties, protocols, and agreements for a little more context.

The Kyoto Protocol was the original international agreement aimed at implementing guidelines for reducing global GHG emissions. It was adopted in 1997, came to be enforced in 2005, and applied to the “commitment period” of 2008-2012. Developing nations, more than 100 of them across the globe, were asked to only voluntarily comply, while 37 industrialized nations plus the European Community, signed to be bound by it. These developed countries of the world had base national emissions rates determined. Most set the base year to 1990, and then all future emissions targets would be based on the set rate. These numbers would hence set a Cap on carbon emissions, unique for each participating nation, and for businesses the government applies a cap to a whole industry. The cap reduces over time in alignment with the increasingly ambitious emissions goals. The government issues permits to the emitters, which are Carbon Credits, where 1 credit equals 1 ton of CO2e. If a nation or business emits less than their permitted allocation, the non-emitted amount of GHGs are Credits which can be traded, sold, or kept for future use. If traded or sold they are part of the Cap-and-Trade system.

Even before the Kyoto Protocol was enforced, companies began using this trading method, which became known as a “pre-compliance” market. Once the Protocol came into force, credits started to be traded on markets backed by a regulatory mandate. These markets, supervised by governmental regulatory bodies, became known as “compliance” markets. It was due to this adoption of carbon trading which has been purported as a reason for rapid uptake of renewable energy.

To demonstrate the success of this marketplace, the European Union’s Emissions Trading System, which initially regulated about 50% of emissions primarily from energy providers and large industrial polluters, saved more than 1 billion tons of CO2e from 2008-2016. In the United States, California is enjoying a 13% drop in CO2e due to a combination of cap-and-trade and strong policy.

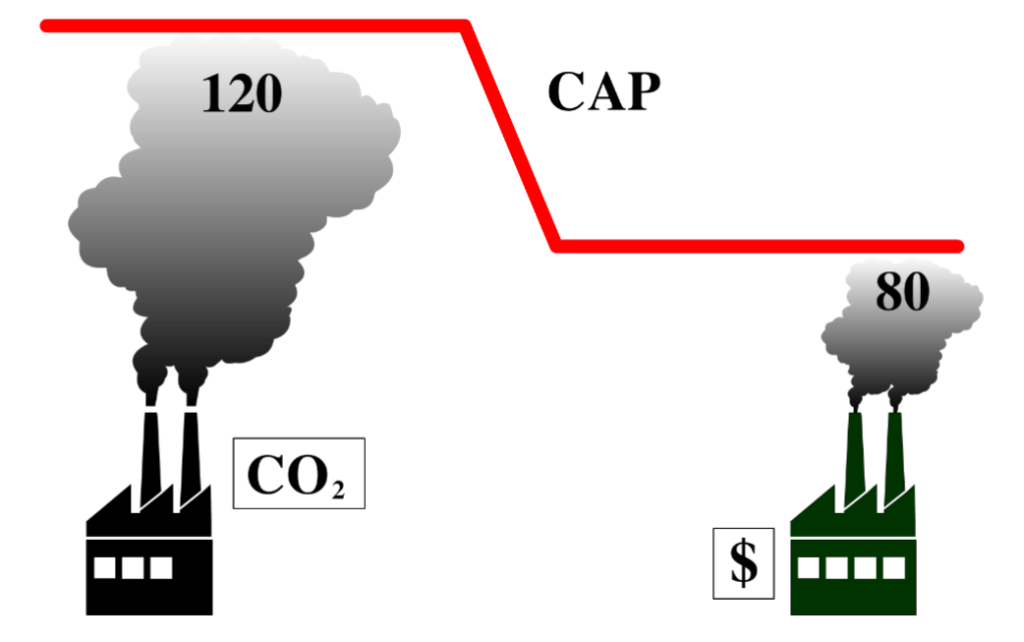

So how does it work? Company A has a cap of 100 units (100 x 1 ton), but they will exceed this and hit 120 units. If they do, they will be fined and taxed heavily. Company B on the other hand, which also has a cap of 100 units, can quickly deploy tech to reduce their emissions to 80 units. Company A can then buy Company B’s unnecessary credits. So long as the cost is less than the would-be fine, this makes perfect sense for both parties. Regardless of who they pay for credits obviously they’d prefer not to have to do this, so there is continued incentive for Company A to address their emissions. Of course this is a simplified explanation. As with all things climate related, the devil is in the detail, and the real-world application of carbon trading is far more complex.

Another option for accessing carbon credits in a trade situation is that Company A approaches a forested land owner who was possibly interested in a deforestation and animal agriculture project. If Company A can pay them on a perpetual basis (while they deploy emissions reductions tech), it’s in the best interest of both parties to leave the land healthily growing carbon-capturing forest.

Buying carbon credits is mandatory in the case where a company will exceed their carbon cap. And that’s the difference between credits and Carbon Offsets – the latter being voluntary. A carbon-reduction project generates carbon credits, and someone then buys it to offset their own emissions from air travel or just from their general lifestyle. As they gain popularity they are popping up all over the place. Demand equals supply. While that’s good in theory, people wishing to buy offsets need to carry out fairly extensive research to know that these projects are what they say they say. Carbon credit projects need to demonstrate that the achieved emission reductions or carbon dioxide removals are real, measurable, permanent, additional, independently-verified, and unique. We recommend looking to Gold Standard, Verra, or Green-e Climate for certification of projects you’d like to use to offset your carbon emissions.

The carbon market has the potential to continue to increase the speed with which we embrace renewable energies. And it has been shown to incentivize emissions reductions. But we feel strongly that this system should be temporary. The main goal should be to reduce emissions in an absolute sense, not just through trading.